Paul Karabinis interview

[et_pb_section bb_built="1"][et_pb_row][et_pb_column type="4_4"][et_pb_image _builder_version="3.0.102" src="http://onetwelvepublishing.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/05/015_dancing-madly-backwards_cyano08jpg.jpg" show_in_lightbox="off" url_new_window="off" use_overlay="off" always_center_on_mobile="on" force_fullwidth="on" show_bottom_space="on" /][et_pb_text _builder_version="3.0.101" background_layout="light"]

I grew up in Gainesville, Florida. In the 1960s it was your classic college town. Everything seemed to revolve around the University of Florida. I spent a lot of time on campus as both of my parents worked there. It was like a small village that had just about everything one needed, even for a kid. I remember going to work with my father and riding all over campus on this fat-tire Schwinn bike he used for running errands. When I tired of that, I would hang around the bookstore or game room or just cruise the smelly stacks of the libraries. In those days Gainesville was a small town where you could ride a bike anywhere, your dog could follow you, and did not have to lock your bike. I know this sounds a bit sappy but growing up in Gainesville was probably not too different from most small towns during this time.

How did you first get into photography?

It started with a Yashica rangefinder my brother handed me when I had to do some now forgotten high school project. All I can remember is that the black and white prints took too long to come back from the camera store and that was very dull and gray. In a matter of weeks, I had a stack of books from the library and was processing film and making prints in the bathroom. The textures of the natural world and my girlfriend were my primary subjects. My interest did not move to the next level until my father found me a job on campus working in a lab charged with providing photographic services for faculty. I was still in high school. This is where I learned everything. The boss was the daughter of a photographer who had served at some level in the Third Reich. She was a perfectionist – always sending me back to the darkroom to redo jobs. I spent my entire time in college working in this lab. Looking back, it was absolutely fabulous as I learned a great deal technically and had almost unlimited access to materials and equipment. The lab was also located within one of the university libraries so I was able to spend a lot of time looking at photography books – mostly the classic European street photographers and photographers of the Farm Security Administration. My work, at the time, was your basic third generation street photography influenced by Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank as well as Winogrand and Friedlander.

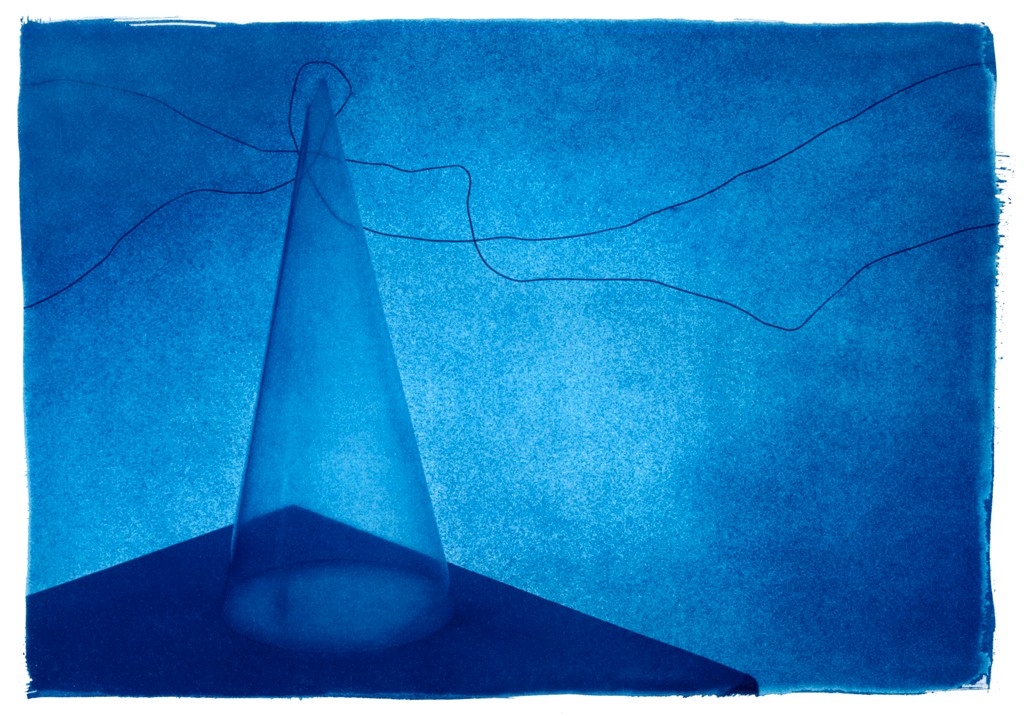

We are featuring your Salt Prints and Cyanotypes, please tell me how you first adopted these processes in your work and why?

The late Todd Walker, who taught at UF in the 1960s and early 1970s, introduced me to historical processes. At the time, I was rather ambivalent about working with these processes as making prints took too long and they just did not look like photographs to me. A growing interest in photo history – particularly the nineteenth century – brought me back to historical processes in the late 1970s. The more I read about photography’s early practitioners, the more it seemed that they understood photography as a hybrid printing process that relied upon light-sensitive chemicals rather than inks.

And once I ceased holding photographs hostage to reality, the visual territory expanded exponentially.

I was also intrigued by the idea of engaging in a different way with the materials of photography. I think I was reacting to how photographic materials were so standardized and beginning to be limited in terms of paper types and surfaces. What really attracted me was the simple act of sensitizing watercolor paper and printing in sunlight. I don’t want to make this seem too precious but working with old processes made me feel like I was actually making something. Every print was different and the visual possibilities seemed unlimited. In time, my understanding of how a photograph could be made, how it could look, and how it might function as a picture changed dramatically. I realized that there was no fixed or definitive “look” a photograph had to have. A picture made with light sensitive materials could look like anything. And once I ceased holding photographs hostage to reality, the visual territory expanded exponentially. That’s the short story of why I am attracted to working with old processes…

Your shift from “reality” picture making to a more historic and ephemeral “old process” seems to coincide with current trends in fine art photography. Do you think it’s safe to assume this has something to do with the “digital age” of photography – or something else entirely?

I believe that digital photography has had a significant effect upon the rise or resurgence of historical processes in a couple of interesting ways. On one hand, the manual nature of making pictures with old processes taps into an ancient sense we have about art as something that is “made” by a human. I just don’t experience this with digital photography and particularly with making a digital print. The control and perfection possible with digital photography have very little appeal to me. I like the uncertainty, the unique look of every print, and the unexpected results that seem to be part and parcel of making pictures using chemicals and light.

The curious thing is that the same digital technology that may have nudged people towards manual processes has also made these processes more accessible. With most historical processes, you have to make your print via contact. Many practitioners work with large format negatives and others go through a process of bumping up 35mm or roll film negatives onto larger sheet film. The latter approach is time-consuming and the results, in my opinion, are just adequate. About four years ago, I began exploring making digital negatives on paper and transparency film. It worked quite well and has proven to be indispensable in my teaching. More important is that this technical breakthrough led to a transformation in how I visualize my pictures.

…photographers and viewers of photography began realizing that a photograph is also as a picture. And like any other kind of picture, photographs need not always reference reality.

Manipulating my images on a computer screen altered my understanding of photography from an act defined by a split second at a given aperture to an open-ended process with unlimited possibilities. To put it another way, I began using the camera to take photographs and the computer to make pictures. This distinction may seem trivial but it has broadened my understanding of how a photograph can be made, how it can look, and how it can function as a picture.

In relation to the shift from “reality” picture making, it seems obvious that software like Photoshop allows users to create pictures that deviate from reality-based picture making. We can’t forget, however, that fabricated or staged photography has been a significant mode in the medium, long before the advent of the digital photo. But what I think happened over the past twenty years or so is that photographers and viewers of photography began realizing that a photograph is also as a picture. And like any other kind of picture, photographs need not always reference reality.

You mentioned you’re early photographic influences. Currently, do you have any peers whose work you respect?

There are a number of photographers I admire but I don’t know if I have been directly influenced by their work. I’ve always liked the sheer intelligence of Duane Michals’ work. I like the inventiveness of Robert and Shana Park-Harrison, and Gregory Crewdson’s work is so wonderfully creepy. I have also enjoyed a lot of the work of Dan Estabrook. I don’t know him but I connect with his visual sensibility and how he uses old processes to create pictures that don’t look contemporary. As far as working with historical processes, he appears to have an acute understand how to match content with process. His pictures appear to be partial documents from another time and place…little fragments that appear significant but are ultimately incomprehensible. That’s my kind of picture. I have to admit, however, that I don’t pay as much attention to contemporary work as I should. My interest is more in the past than the present. I am attracted to a handful of Czech photographers…Jaromir Funke, Frantisek Drtikol and others working between the two world wars. I am also interested in nineteenth-century photographers – part nineteenth-century French Primitives and British Amateurs of the 1840s and 1850s.

You have a quite a bit of curatorial experience, what motivates you to not only be an artist but be also be an art advocate?

If all of your professional life has revolved around the arts and art education, it only seems natural that you would be an art advocate. I ran a small university gallery for twenty-five years and all my energy was directed towards producing exhibitions that would be intelligible and interesting to the general public while accommodating the desires of the artist. I also taught photography and photo history during this period. Most of the time, both aspects of my job were quite satisfying even if I felt frustrated because I wanted more time to devote to my own work. Now that I am teaching full-time and have more time to devote to my own work, I find that most of my energy is directed toward teaching. My own work is important to me but I just can’t imagine devoting myself to it exclusively. I like to think that I have naturally moved towards what I do best – teach – which is a very important kind of advocacy.

I like to think that I have naturally moved towards what I do best – teach – which is a very important kind of advocacy.

What do you find is the most rewarding thing about being a professor in photography?

It’s pretty damn corny but I just love seeing a student get excited about what they are doing. Teaching technique is easy. What’s difficult is figuring out how to establish an atmosphere in which a student can get genuinely excited about the complexities and rewards of making pictures. When this happens, the teacher-student relationship shifts into a special territory were each starts learning from the other. I don’t have a specific recipe for how to make this happen but I introduce students to history and a little theory, make them write about their work, direct them to others who have similar interests, and try to continue the conversation about their work and photography beyond the confines of the classroom. As I indicated above, teaching technique is not that hard to do. Oftentimes, this is all a student wants or all they can handle. That’s just the way it is and I don’t let it affect my overall agenda. I try to remember that everyone has different motives for being in school of for what they want to do with photography – and I try to be as helpful as I can regardless of their level of interest.

View the exhibition

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]